A Brief Reflection of Psychoanalytic Therapy

I’ve been asked many times what psychoanalytic treatment can offer. With time, I have come to wonder less about what this experience offers, and much more about how it is able to offer anything at all.

Psychoanalytic treatment can offer a space for silence, stillness, and clarity; but it does so by waiting like a discharge valve for tension. It can be a holding cell for chaos; but will not simply hold our lives on our behalf, or in our absence. We must not only express but share, explore, and experience to achieve relief. And at its most basic level, this process - exciting, messy, and full of life as it may be - requires only that both patient and therapist try, to the best of their present ability, to be honest.

That is, of course, a taller order than it would appear; perhaps monumentally taller than we ever understand before attempting it. There are good reasons for that challenge. By the time most of us seek therapy, we are unlikely to carry the shameless transparency of toddlerhood – that one, breathtaking moment when we have developed the language to express ourselves, but have not internalized any prohibitions against doing so.

Under the best circumstances, we are generally amused by the social faux pas when a child openly declares their distaste, announces their bodily functions, or throws themselves to the ground in rage and disappointment. We can, if only after our immediate embarrassment has passed, smile at their openness. We understand implicitly that exercising restraint requires great effort.

But we may also smile because we are witnessing an insight, honesty, and sense of security that we know we have lost. It is easy to assume that if we wanted to express ourselves so freely, we could; to believe our restraint is a choice. We may prefer to be blissfully unaware that such openness is as difficult for us as restraint is for a child.

Our public discretion is, of course, a developmental accomplishment. It is born out of both our better cooperative and empathic instincts, but also our deep, primitive fear of rejection and isolation; perhaps out of even deeper fear about our own worthiness of such acceptance or rejection.

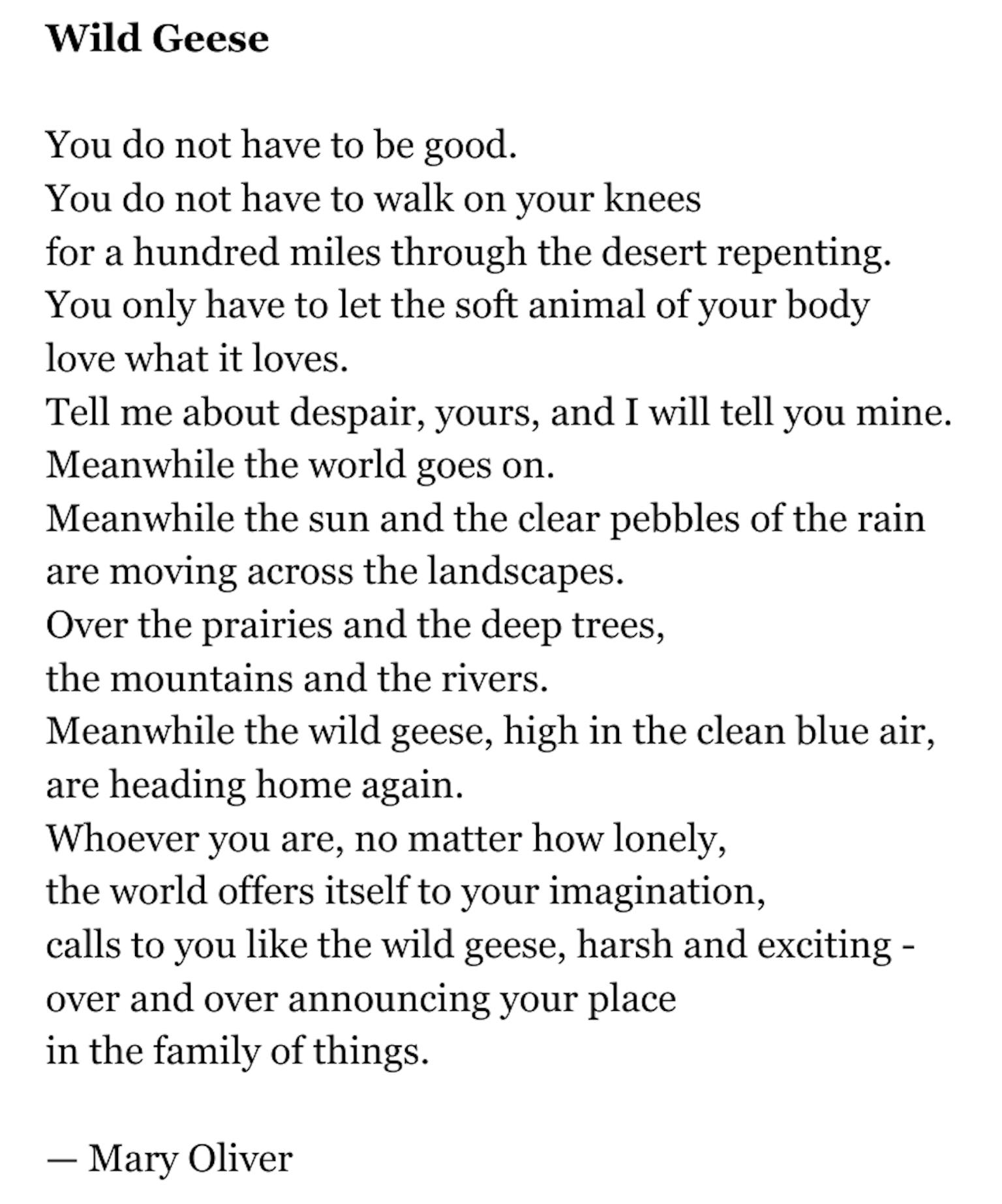

And this public discretion, years in the making, also means we have learned shame, embarrassment, and a constellation of personal feelings, fears, and beliefs that come together to inhibit the exposure of deeply honest relationships and discourse. This, perhaps, is where psychoanalysis at its best makes us a different offer. It offers us a basis of acceptance and curiosity. It takes as its opening, and most basic assumption, the lines from Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese:

You have, after all, a choice. And, with that, it asks us to challenge fear, shame, and repentant containment. You have proven your restraint; now prove you can release yourself.

Jordan Ainsley, PhD

Jordan is a psychologist with nine years of clinical experience and a doctorate in Counseling Psychology from the University of Miami, one of the nation’s longest-standing APA-accredited programs. She is also completing advanced training at the Florida Psychoanalytic Center, known for its long tradition of rigorous clinical education.

Jordan says, “I aim to provide a safe, supportive environment for openly examining thoughts, feelings, and experiences, so you can come to understand, and make choices around, the patterns shaping your life.”